In 1992, Kenneth Rouse, an African-American man with an IQ between 70 and 80 - "borderline intellectual functioning," in the clinical parlance - prepared to stand trial in North Carolina on charges that he had robbed, murdered and attempted to rape a white, 63-year-old store clerk.

Rouse's lawyers questioned the prospective jurors to try to expose any racial or other bias they might have against the defendant. But several years after the all-white jury convicted Rouse and recommended a death sentence, his defense team made a stunning discovery.

One of the jurors, Joseph S. Baynard, admitted that his mother had been robbed, murdered and possibly raped years before. Baynard had not disclosed this history, he said, so that he could sit in judgment of Rouse, whom he called "one step above a moron." Baynard added that he thought black men (“niggers” was the term he was quoted as using) raped white women for bragging rights.

As claims of juror bias go, the evidence could hardly have been stronger. But Rouse's final appeal was never heard. Under the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996, Rouse's lawyers had just one year after his initial state appeal to petition for a last-resort hearing in federal court.

They missed the deadline by a single day.

A federal appeals judge wrote that it was "unconscionable" for her court to reject Rouse's case because of such a mistake by his court-appointed lawyers. But dozens of lawyers have made the same mistake, and most of their clients, like Rouse, have not been forgiven by the courts for missing the deadline.

An investigation by The Marshall Project shows that since President Bill Clinton signed the one-year statute of limitations into law - enacting a tough-on-crime provision that emerged in the Republicans' Contract with America - the deadline has been missed at least 80 times in capital cases. Sixteen of those inmates have since been executed -- the most recent on Thursday, when Chadwick Banks was put to death in Florida.

By missing the filing deadline, those inmates have usually lost access to habeas corpus, arguably the most critical safeguard in the United States' system of capital punishment. "The Great Writ," as it is often called (in Latin it means "you have the body"), habeas corpus allows prisoners to argue in federal court that the conviction or sentence they received in a state court violates federal law.

For example, of the 12 condemned prisoners who have left death row in Texas after being exonerated since 1987, five of them were spared in federal habeas corpus proceedings. In California, 49 of the 81 inmates who had completed their federal habeas appeals by earlier this year have had their death sentences vacated.

The prisoners who missed their habeas deadlines have sometimes forfeited powerful claims. Some of them challenged the evidence of their guilt, and others the fairness of their sentences. One Mississippi inmate was found guilty partly on the basis of a forensic hair analysis that the FBI now admits was flawed. A prisoner in Florida was convicted with a type of ballistics evidence that has long since been discredited.

Just last month, Mark Christeson, a Missouri inmate whose lawyers missed the habeas deadline in 2005, received a stay of execution from the Supreme Court just hours before he was set to die by lethal injection.

In a court brief filed on Christeson's behalf, 15 former state and federal judges emphasized that he had not even met the appellate attorneys handling his federal case until after the filing deadline had passed. "Cases, including this one, are falling through the cracks of the system," they wrote. "And when the stakes are this high, such failures unacceptably threaten the very legitimacy of the judicial process."

The 80 death-penalty cases reviewed here were largely culled from databases of federal court opinions, but they also include other, unpublished rulings that were known to capital defense attorneys and advocates interviewed around the country. They represent just a fraction of the habeas appeals foreclosed by the 1996 law, which also applies to non-capital cases.

Like Rouse, who is still awaiting execution in North Carolina, two other inmates missed the habeas deadline by a single day, and for the most banal reasons. One attorney made the mistake of using regular mail instead of an overnight courier; another relied on a court's after-hours filing system, which turned out to be broken.

But many of the other habeas petitions from condemned inmates were late by hundreds of days, or even thousands. (On average, those lawyers missed the deadline by 853 days, or more than two years and four months.) In one case, the attorney was more than 11 years late.

Some of the lawyers' mistakes can be traced to their misunderstandings of federal habeas law and the notoriously complex procedures that have grown up around it. Just as often, though, the errors have exposed the lack of care and resources that have long plagued the patchwork system by which indigent death-row prisoners are provided with legal help.

The right of condemned inmates to habeas review "should not depend upon whether their court-appointed counsel is competent enough to comply with [the] statute of limitations," one federal appeals judge, Beverly B. Martin, wrote in an opinion earlier this year. Allowing some inmates into the court system while turning others away because of how their lawyers missed filing deadlines was making the federal appeals process "simply arbitrary," she added.

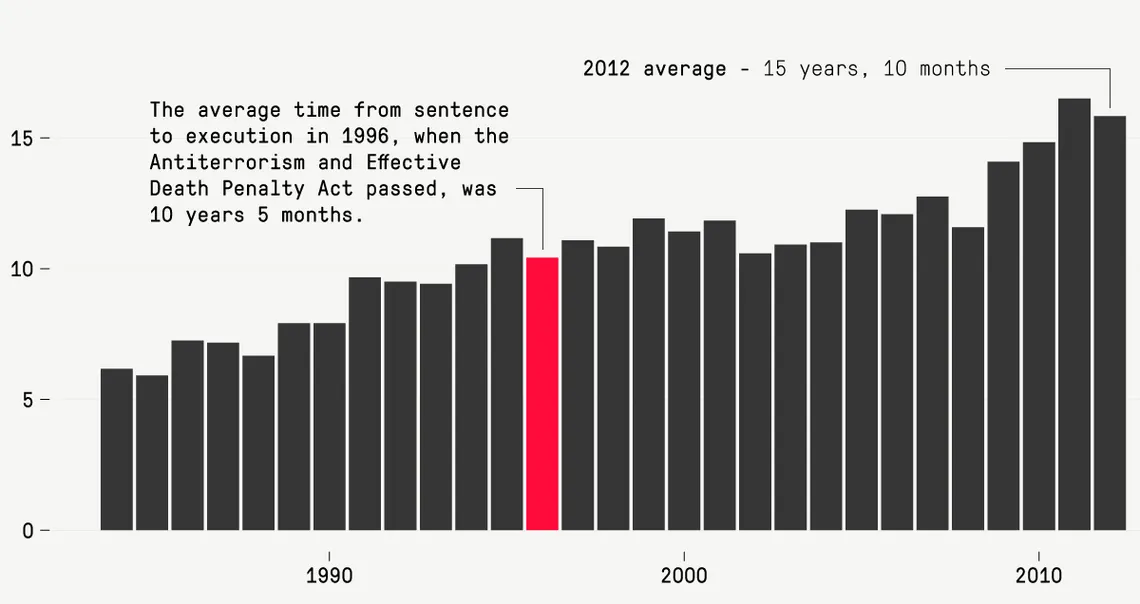

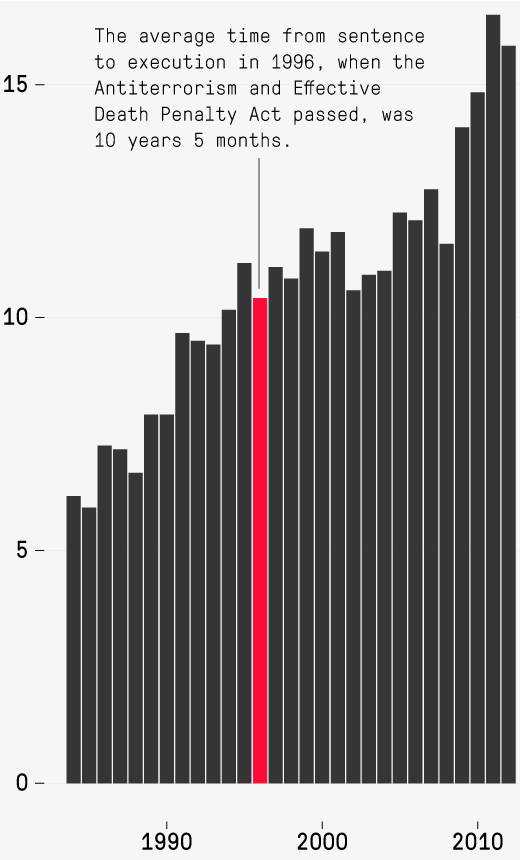

Meanwhile, the problem that the habeas deadline was intended to solve - the ever-lengthening delays in the carrying out of death sentences - has grown steadily. In 1996, the average time from sentencing to execution was 10 years and five months, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics. In 2012, the latest year for which the same figure is available, the delay had stretched to 15 years and 10 months.

SOURCE: BUREAU OF JUSTICE STATISTICS

SOURCE: BUREAU OF JUSTICE STATISTICS

The 1996 law that set the one-year statute of limitations on habeas appeals was one of the signal compromises that Clinton forged on domestic policy in the aftermath of the sweeping Republican victory in the 1994 midterm elections.

Some Republicans had advocated for habeas corpus reform for years, mainly as a way to streamline and limit death-row appeals. The idea struggled to gain traction, but it became a small element of the Contract with America championed by then-Rep. Newt Gingrich (R-Ga.), who was on his way to becoming House speaker. After the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995, the proposal found new life as part of antiterrorism legislation embraced by both parties.

That pairing created political tension, both between the major parties and within them. Some Democrats supported the antiterrorism measures but viewed the habeas restrictions as the unnecessary circumscribing of a fundamental right. Some Republicans backed the habeas restrictions but feared the possible government excesses that might come from expanding surveillance authorities and other law enforcement powers also included in the measure.

"Why is it necessary to link the death penalty and the constitutional guarantees of habeas corpus to a terrorism bill?" Rep. Joseph P. Kennedy II (D-Mass.) asked during the debate in the House. "This is just a political deal. It is a political deal to get votes on the right."

By the mid-1990s, American support for the death penalty had climbed to 80 percent, its highest point since Gallup began polling on the issue in the 1930s. Public patience with the appeals process also was waning as the typical time between sentencing and execution stretched to more than a decade.

"Somehow, somewhere, we are going to end the charade of endless habeas proceedings," the chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, Rep. Henry J. Hyde (R-Ill.), declared in the debate over the antiterrorism law. "And this bill is going to do it."

But important changes in the legal landscape already were raising concerns among some civil libertarians. One opponent of the habeas proposal, Rep. Melvin Watt, a North Carolina Democrat, cited the advent of DNA evidence and the fact that some prisoners were being exonerated up to 15 years after their trials. Congress, he said, was proposing "to compromise the most basic thing - innocence - for political expediency."

Four former U.S. attorneys general who were opposed to the legislation - two Democrats and two Republicans - wrote to Clinton to urge that any filing deadlines on habeas petitions take effect "only upon the appointment of competent counsel."

As supporters of the bill lined up four competing attorneys general behind their position, Hyde announced that he had a "celebrity to trump all of those attorneys general" on the matter. "His name," Hyde said, "is President Clinton."

Clinton, who had initially opposed linking habeas reform to the antiterrorism measures, changed his mind - as he had on key facets of welfare reform, criminal sentencing and other domestic policies. As he began campaigning for reelection, he described the delays in death-penalty litigation as "ridiculous." The streamlining of appeals should begin with the Oklahoma City bombing cases, he announced.

The ranking Democrat on the Senate Judiciary Committee, Joe Biden of Delaware, introduced amendments to soften several of the habeas restrictions in the bill. At one point, he proposed to limit the one-year deadline to only federal prisoners, but he eventually supported the bill that came to the floor without that change.

The legislation passed the Senate by a vote of 91 to 8, and it cleared the House by a margin of more than two to one.

The hurried and often convoluted draftsmanship of the law's habeas provisions began to come under criticism almost as soon as it took effect. The ambiguities of the measure left a host of questions for the courts to answer, and with each passing year, the relevant case law has grown more complex.

Under the 1996 law, the one-year statute of limitations to file a federal habeas petition is supposed to begin after the conclusion of an inmate's direct appeal, which is filed in the state courts.

The direct appeal - the first of three levels of possible appeals - must focus on the trial record. It can argue, for example, that an important objection by the defense counsel should have been sustained rather than overruled.

Post-conviction petitions, which include federal habeas corpus appeals, can go beyond the trial to deal with anything from new evidence to the discovery of juror misconduct.

Lawyers who do post-conviction work in capital cases face a daunting array of challenges: They must typically reinvestigate the evidence for both guilt and punishment; canvass witnesses called and uncalled; plumb a defendant's criminal, social and family history; and round up and study thousands of pages of records. They must also navigate an ever-shifting landscape of appellate deadlines and procedures, identify promising issues and craft a detailed petition - all while under the pressure of defending a client whose life may depend on their success.

Yet while the law guarantees that indigent death row inmates have a court-appointed attorney in federal habeas corpus proceedings, it does not stipulate that the attorney must be competent. The Constitution guarantees the effective assistance of counsel at trial, but gives no similar assurance for lawyers doing habeas work.

Some of the same federal judges who are responsible for appointing habeas counsel have later traced the failure of such attorneys to meet the filing deadline to their inexperience, indifference, ineptitude or illness - and to myriad combinations thereof.

Motions or petitions filed properly in the state courts can suspend the federal deadline. But sometimes the motions are filed improperly, with lawyers neglecting to secure authorization to practice in a given court or failing to pay a required filing fee.

In at least three cases since 1996, attorneys filed papers in the wrong court. One appellate attorney discovered that his predecessor missed the habeas deadline after failing to even order the client's case file. Another attorney, who insisted that he had read the relevant case file, was later found to have never picked up the voluminous records from a state repository.

In some of the 80 cases, mistakes by judges compounded those of defense attorneys.

The lawyer for Richard Hamilton, who was convicted in 1995 of raping and murdering a 23-year-old nursing student after kidnapping her from a supermarket parking lot in Lake City, Fla., thought Hamilton had more time to file than he really did. So did a local judge, who told Hamilton not to worry. "It has been resolved," the judge said, to which Hamilton replied: "If you say so, that's good enough for me."

In two cases out of Texas, U.S. district court judges granted requests for a filing extension - setting, in effect, what appeared to be a new deadline - then enforced the old deadline after the petition was filed. "Parenthetically, this court may have erred in assuming that it had the authority to extend the statutory deadline," one judge later acknowledged.

Sometimes, courts waited too long to appoint habeas counsel. In California, where the courts have struggled mightily to find attorneys for capital appeals, at least six inmates received an attorney only after their deadline had passed - by more than five years in two cases.

Then there are lawyers who have failed even more basic scrutiny.

Some of the attorneys appointed to the 80 cases include an Alabama lawyer who was addicted to methamphetamine and was on probation for public intoxication, and a Louisiana lawyer who suffered from a neurological and physiological disorder so debilitating that he was asked to leave his firm.

One attorney in Texas had twice before been reprimanded for misconduct, while another Texas lawyer had twice been put on probation by the state bar. Two weeks after being appointed in the capital case, he was put on probation again.

In Mississippi, Willie Jerome Manning's first appointed attorney withdrew, citing his "most limited knowledged [sic] and familiarity with post-conviction proceedings at all." A second attorney also withdrew, citing his lack of qualifications. A third attorney was appointed - by a court order that was misfiled, adding to the delays - seven months after Manning's habeas deadline.

Two other men facing death sentences complained that their lawyer had a drinking problem - and they had the same lawyer. "Damn near fell out of his chair," one of the inmates wrote of the man in a letter to the lawyer's co-counsel.

As deadlines approached, some inmates pressed their attorneys for information. "I'm getting a little worried," one wrote. Another pleaded, "I want to know what's going on!" Chadwick Banks, the inmate executed in Florida on Thursday, wrote his attorney three weeks before his filing deadline, asking about “some date” that he understood could make a “big difference.” (Ultimately his appeals deadline was missed by 2,079 days.)

In several cases, courts have shown that prisoners who schooled themselves in habeas law have sometimes demonstrated a better understanding of legal intricacies than their lawyers.

"[P]lease file my 2254 Habeas Petition immediately," one defendant wrote in a typical plea to his lawyer. "Please do not wait any longer . . . again, please file my 2254 Petition at once."

The Supreme Court took note of the phenomenon in the case of Albert Holland, who was sentenced to death for the 1990 murder of a Florida police officer who tried to arrest him.

"Holland was right about the law," the justices wrote. His lawyer, they added, "was wrong about the law."

In the tracing of blame, the case of Mississippi death-row inmate Alan Dale Walker offered a triple bank shot. Attorneys for the state put a wrong date in a court filing. The Mississippi Supreme Court incorporated that error into an opinion. An attorney for Walker then used the opinion to calculate the filing deadline.

Walker had a second attorney who had separately calculated the deadline, without relying on the court's opinion. He came up with a different date - but his date was wrong, too.

The struggle to find capable lawyers for capital cases has been particularly visible in a handful of states with large numbers of death-row inmates.

Since its death penalty was reinstated in 1976, Florida, for example, has bounced from one troubled arrangement to another for the provision of post-conviction counsel. Of the 80 capital cases with a missed deadline, Florida has 37 - the most of any state by far.

The state originally asked private lawyers to do the work free; it got few takers. It then established a special government office to do the work, but later shifted much of the load to a registry of private attorneys after lawmakers complained about the delays and the cost. In 1998, the state also set a cap on the number of hours per case those lawyers could bill (840) and the rate they could charge ($100 per hour).

The complexities of habeas law often have challenged even the most conscientious defense attorneys.

Michelle Kraus is an experienced defense attorney in Fort Wayne, Ind., who concentrates almost entirely on trial work. At the request of a lawyer friend, she signed on to assist with a state-level appeal for Gregory Scott Johnson, who had been convicted in 1986 of beating an 82-year-old woman to death. But after her friend left the case, Kraus wound up taking it to federal court, where she confronted a steep learning curve.

"It was overwhelming, getting grounded in it," Kraus says. She got the standard text on habeas practice and procedure - at that point, the two volumes ran to some 2,000 pages - and read it front to back. She also traveled to Atlanta to attend a one-week seminar on capital litigation, taught by some of the country's leading experts.

Kraus devoted long hours to Johnson's petition, which included a claim that prosecutors failed to disclose evidence that might have reduced Johnson's culpability and perhaps spared him the death penalty. She dropped the petition in the mail three days before deadline, but it arrived one day late.

"Counsel bungled the job," the federal appeals court wrote in 2004. Instead of using first-class mail, Kraus should have opted for FedEx or a courthouse messenger, the court said. The person held accountable would be Johnson. "[L]awyers are agents," the court wrote. "Their acts (good and bad alike) are attributed to the clients they represent."

Telling Johnson about her mistake - and how he would be punished for it - "was probably the hardest thing I've ever done," Kraus says. She stayed on the case - "he forgave me," she says - and was with Johnson for his last meal before he was executed in 2005.

But Kraus has declined to do any more habeas work since then.

"The pitfalls are there, and I fell into one," she recalled. "And it was horrible."

Sometimes, even legal organizations that are usually lauded for the quality of their capital work have faced criticism.

In a Georgia case, a federal judge chastised lawyers with the Southern Center for Human Rights, a nonprofit that opposes the death penalty and provides free legal support to prisoners in capital cases. The Southern Center lawyers had left the case well before an inmate's habeas petition was due, but the judge argued that they should have done more to find replacement counsel and to help the inmate determine the filing deadline.

One of the authors of the two-volume legal guidebook on habeas practice, James S. Liebman, a law professor at Columbia University, says the complexity and vagueness of the 1996 law has given lawyers all kinds of procedural nuances over which to fight. An important result has been that prosecutors have more ways to get a petition thrown out on procedural grounds - an advantage that they have seized "energetically and assiduously," Liebman says.

The guidebook, now in its sixth edition, has grown over the years to 2,700 pages. "There are more and more pages,” he said, but “less and less justice."

Confronted with late filings, courts have embraced a remedy called "equitable tolling," which allows judges to waive a missed deadline in some circumstances. But courts limit its application to extraordinary situations, and the standard has been applied unevenly around the country.

Plain negligence - or a "simple gaffe," as the court labeled the mistake Kraus made - generally will not merit a judge's forbearance. But abandoning clients or lying to them often will constitute grounds for setting the deadline aside.

In the 80 capital cases, courts have granted equitable tolling in about a third. At least three of the inmates whose habeas petitions were reviewed went on to receive new trials.

The courts usually won't forgive a missed deadline if an attorney misinterpreted the law, a mistake that gets categorized as negligence. But a federal court in Ohio did so in the case of Michael Keenan, a landscaper who was convicted of murdering a young man found in a Cleveland park. "He would have been executed," Keenan's lead defense lawyer, Vicki Werneke, said in an interview. "He came dangerously close to getting his whole case dismissed."

When Werneke came onto the case in 2008, after Keenan had been granted equitable tolling, the state's case was already showing signs of unraveling. In 2012, a U.S. district court judge considered Keenan's habeas petition and ordered a new trial. Citing the state's "egregious prosecutorial misconduct" in withholding evidence, an Ohio county judge later ruled that prosecutors can't retry Keenan, allowing him to go free.

The state's appeal of that ruling is now pending before the Ohio Supreme Court.

When a deadline is missed, an inmate's federal appeal can be lost - no matter the strength of the argument for a new trial, and even if the late filing can be attributed more to hard luck than ineptitude.

The law requires that prosecutors turn over evidence favorable to the defense before trial. But it wasn't until 22 years after William Kuenzel was condemned in Alabama that his appellate attorney received police notes and grand jury testimony undermining the prosecution's case.

Kuenzel was convicted in 1988 of murdering a convenience-store clerk. But in 2010, the state disclosed that an alleged accomplice originally told police he was with someone else, and that the only eyewitness who identified Kuenzel at trial had told grand jurors she "couldn't really see a face."

With such revelations, Kuenzel's claim of innocence has attracted an array of prominent supporters and generated a polished publicity campaign. Three former district attorneys - Robert M. Morgenthau of Manhattan, Gil Garcetti of Los Angeles and E. Michael McCann of Milwaukee - filed a brief with the Supreme Court saying the newly surfaced evidence "completely eviscerated" a prosecution case that they characterized as “weak, to say the least."

Although Kuenzel now has potentially strong grounds for an appeal, he still lacks a court to hear them - his lawyer missed the federal filing deadline by nearly three years.

When the 1996 law took effect, Kuenzel had one year to file his habeas petition. But the law included a provision that would suspend the normal one-year statute of limitations if an inmate had a "properly filed" petition pending in state court, effectively stopping the clock on the appeals process.

A petition that Kuenzel had filed in an Alabama circuit court had been dismissed as untimely in 1994, but then restored to the docket in May 1996. This led Kuenzel and his attorney to believe he had a "properly filed" state petition pending, and that the countdown toward the appeals deadline had paused.

But three years later, the circuit court reversed itself again at the request of state prosecutors, which was interpreted by a federal court to mean that the clock had been ticking all along.

"It is just the most grievous injustice," says David Kochman, an attorney who has been working on Kuenzel's appeal since 2004. "If any case was crying out for review, it was this case."

The state has written in court files that the newly disclosed evidence "fails to even come close" to exonerating Kuenzel. "It is time for this case to finally come to an end," wrote the state, which two months ago asked for an execution date to be set.

Sentenced to death at 26, Kuenzel is now 52. In a letter to this reporter last month, he wrote that he felt like he was listening to an old grandfather clock as it wound down, knowing he would be killed when it stops. He can't rewind the clock, he said, because "the courts have shut the hole."

On April 17, 1996, as then-Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan argued against any weakening of habeas corpus protections in the pending antiterrorism bill, the New York Democrat reminded his colleagues that the matters at hand were more profound than mere legal procedures.

"We are dealing here, sir, with a fundamental provision of law, one of those essential civil liberties which precede and are the basis of political liberties," Moynihan said.

Quoting from a letter that several former attorneys general had written to President Clinton, he cast the federal courts' ability to review state-court decisions under habeas corpus as an essential guarantee: "It has a proud history of guarding against injustices born of racial prejudice and intolerance, of saving the innocent from imprisonment or execution, and in the process, ensuring the rights of all law-abiding citizens."

Two days before Moynihan's speech on the Senate floor, one of the jurors who voted to send Kenneth Rouse to his death, Joseph Baynard, signed an affidavit acknowledging that he had deliberately withheld the fact of his mother's murder so that he could get on the jury.

Baynard, who died last year, acknowledged in the affidavit that his decision in the Rouse case might have been colored by "bigotry." A Duke University law student who interviewed the former juror for Rouse's appeal also filed a separate affidavit detailing Baynard's racial invective.

At that point, Rouse's case was still in the state courts, which ultimately denied him a new trial. His one-year habeas deadline came on Feb. 7, 2000, and his lawyers, who miscalculated the date, filed their petition on his behalf one day too late.

While the American public often complains about criminal defendants winning their legal cases on technicalities, the opposite is often true, says Gretchen Engel, a habeas expert who had advised Rouse's defense team and provided the correct filing date: "What they don't realize is how often people lose on technicalities, or in ways that would offend most people's sense of justice."

Despite the federal courts' refusal to hear his case, Rouse got one more chance in 2009, when the North Carolina legislature passed the Racial Justice Act, allowing condemned prisoners to challenge their sentences if they could demonstrate that racial bias had played a role.

Rouse filed a motion to have his case reviewed under the act. But in 2013 - after four other death-row inmates had succeeded in getting their sentences reduced to life without parole under the new provision - the state legislature repealed the law altogether.

Rouse's motion is still pending. It is unclear if it will ever be heard.

This is part one in a series. Read part two.