Kelsey Lindroth grew up in Suffolk County, Long Island, in the middle of a burgeoning heroin epidemic. She started with painkillers, and by 15, she had moved on to heroin. Now, at 24, Lindroth is sober, largely with the help of a new medication, Vivitrol, that blocks her opiate receptors. Even if she uses, she can’t get high.

Every month, Lindroth receives an intramuscular injection of Vivitrol, which lasts for about 30 days. It was prescribed to her by a treatment provider, and she says she hasn’t used heroin since receiving her first shot in June 2013. “For me, it felt like Vivitrol changed the way my brain worked.”

Last month, Suffolk County officials announced a program to incorporate Vivitrol at all levels of the criminal justice system. Officials from the drug courts, the probation office, and the sheriff’s department are developing procedures to recommend Vivitrol to addicts, when appropriate, and have been meeting with pharmaceutical representatives from the drug’s manufacturer, Alkermes.

Opiate addiction has hit Suffolk County hard; nearly 700 people have died from painkillers and heroin between 2012 and 2014, many of them young adults and teenagers. Others often end up in handcuffs, in front of judges, and later, in jails and prisons. Meanwhile, Vivitrol programs have launched in at least 26 states and will soon be permitted in places -- including Suffolk County’s jails -- where other medical treatments for heroin addiction have long been banned.

The increasing popularity of the drug represents a shift from the prevailing therapy, which employs the opiate-based substitutes Suboxone and methadone. They diminish withdrawal and suppress the effects of heroin and painkillers. Both drugs have proven effective at combating opiate abuse, yet many see these treatments as replacing one addiction with another, and judges and law enforcement have long resisted programs that put addicts on opiate-based medications to aid their recovery. “We kept catching inmates trading [Suboxone],” says Suffolk County Sheriff, Vincent DeMarco. “It became a currency.”

A recent investigation by the Huffington Post documented the hurdles that addicts face when trying to get on opiate-based therapies, which are prohibited by some drug courts. Shortly after the story, the White House's Office of National Drug Control Policy said it would withhold federal funding from drug courts that refuse to allow addicts to attend programs that use medication-assisted treatments. According to a national survey published in 2013, 56 percent of drugs courts offered such treatments.

However Vivitrol, which has no street value, has led some judges to rethink their resistance to addiction medications. In Nassau County, Long Island, where a similar heroin surge is playing out, Judge Frank Gulotta’s strict policies caused controversy last year when a drug court participant died from a heroin overdose after Judge Gulotta required he get off methadone in order to stay in the program. Judge Gulotta allows Suboxone for those who have already been prescribed it by a doctor, but they must wean themselves off it in order to graduate. Vivitrol, however, is permitted. (Judge Gulotta would not answer specific questions about how the drug is used in his courtroom.)

Vivitrol is expensive — $800 to $1,200 per dose, one dose per month — especially when compared to other addiction medications. Suboxone can cost between $100 to $500 per month, while methadone averages around $300 per month. Most insurance providers and state Medicaid plans will cover Vivitrol, but at the Suffolk County jail, inmate health costs are the responsibility of taxpayers. The county is hoping Alkermes will provide the inmates’ supply for free.

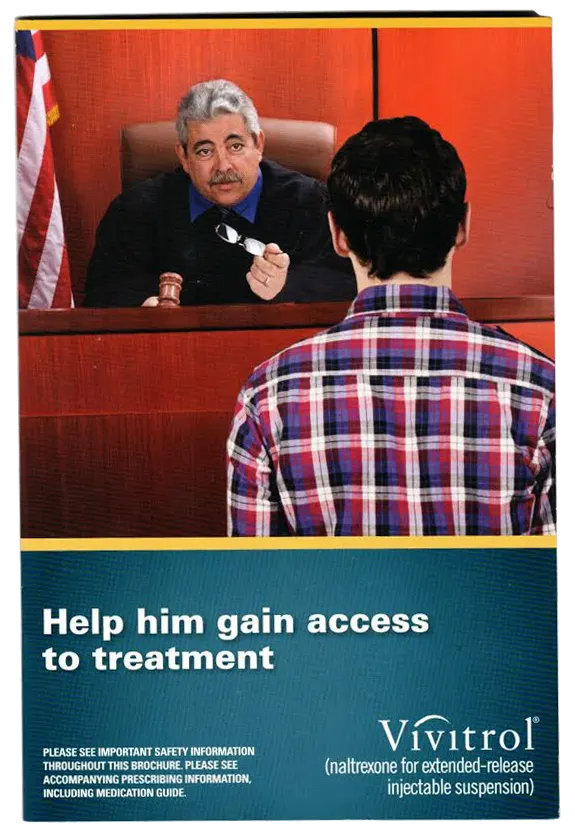

It’s not an unusual request. Alkermes provides Vivitrol at no cost to pilot programs in drug courts and jails around the country, many of which have produced positive results that the company uses to market its drug. Usually, pharmaceutical sales representatives visit doctors’ offices to sell their products, but Alkermes makes its pitch to judges, sheriffs, and others who might recommend Vivitrol to the addicts arrested in their communities. An Alkermes brochure about Vivitrol features a judge talking to a young man with the caption, “Help him gain access to treatment.”

The marketing of the drug makes some law enforcement officials wary. Last summer, Alkermes held a paid presentation at the American Legislative Exchange Council conference, a consortium of lawmakers and private companies that drafts pro-business legislation for introduction at the state level. “It makes me think of a Latin phrase cui bono,” says Suffolk County drug court Judge William Ford. “Meaning, who stands to benefit?”

Others find the company’s promotion of the drug encouraging. “Alkermes proved to the industry there’s money to be made saving the lives of addicts,” says Doug Marlowe, chief of science, law and policy for the National Association of Drug Court Professionals. “Up until recently, the only people who worked with addicts were bleeding heart psychologists and social workers like me.” He points out that Reckitt Benckiser, the maker of Suboxone, is also working with drug courts.

One of the most frequently cited Alkermes partnerships is with the Barnstable County Correctional Facility in Massachusetts, which has treated over 100 inmates with Vivitrol since 2012. Barnstable Sheriff James Cummings estimates that more than 50 percent of inmates who have received the drug over the past two years have remained sober, while relapse rates for opiate addicts with no medication are around 85 percent. Only 20 percent of those who received Vivitrol at the Barnstable jail have been reincarcerated, he said. Alkermes provides the shots for free.

Suffolk County has approved a similar program, says DeMarco. Inmates would be injected with Vivitrol about a week before discharge. They would then be set up with an aftercare plan and assistance signing up for insurance so the next month’s shot would be guaranteed.

Vivitrol has its downsides. In rare cases, it can cause liver failure or hepatitis. Unlike methadone and Suboxone, Vivitrol is only offered after the addict completes withdrawal; a shot of Vivitrol before withdrawal can force the body into agonizing days of detoxification. Also, a person who is injured while on Vivitrol will not respond to opioid pain medications. (Addicts on Vivitrol wear tags to inform emergency medical personnel.)

Kelsey Lindroth has experienced those drawbacks. Despite being warned, she used heroin the night before her first Vivitrol shot and was immediately sent into withdrawal. She recently got in a car accident, and was unable to receive opiate-based medications to deal with the pain.

Both were small prices to pay, she says. After six stints in rehab, and attempts at getting clean through both abstinence and Suboxone, Lindroth says she is now finally free. She credits Vivitrol with kicking her $600-a-day habit, which she supported by stealing and selling drugs. “Without it, I would be in prison or dead,” she said.

But Lindroth also attends Alcoholics Anonymous and counseling, and has restructured her life to avoid temptation. Her substance-abuse counselor, Elsa Pfeifer, who works at the Kenneth Peters Center for Recovery, says the biggest mistake people make is thinking Vivitrol is a one-step solution.

“It’s supposed to be part of a whole treatment protocol,” says Pfeifer. “Kids think they won’t have to do the work, that this is a magic bullet. It’s not.”