More than any other media industry, Hollywood has shaped how the American public views crime and punishment. When we think about serving on a jury, we think about 12 Angry Men. When we worry about serial killers — in reality, a vanishingly small number of murderers — Hannibal Lecter looms large. And much of our cultural knowledge about Italian organized crime ties back to The Godfather trilogy (the Italian-American community, by the way, isn’t thrilled to be so strongly associated with law-breaking).

At the awards this Sunday, the only Best Picture-nominee with an arguable tie-in to criminal justice — and it’s a thin one — is American Sniper, which bolsters sympathy for the plight of veterans just as the veteran who allegedly murdered the film’s hero, Chris Kyle, currently faces trial. Actor Robert Duvall has also been nominated for his work in The Judge, about a big city criminal defense lawyer who returns to rural Indiana and represents his father in a murder trial. And then there’s actress Rosamund Pike’s nomination for Gone Girl, a thriller about murder, kidnapping, and abuse.

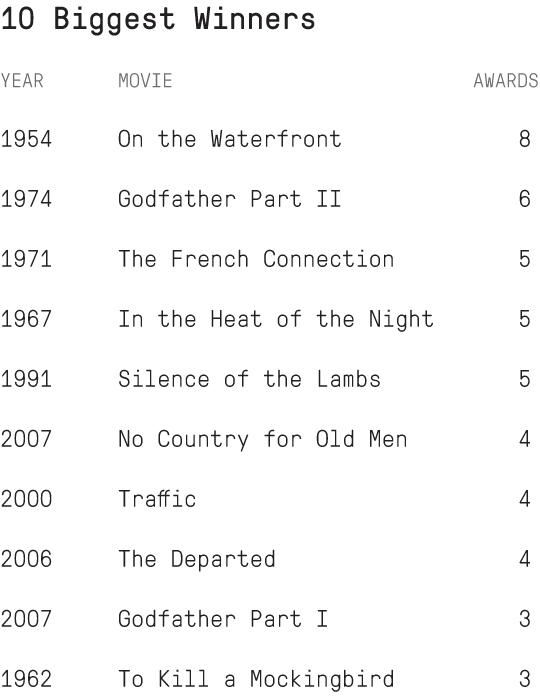

Films have always responded to social and political climates, and a fear of crime has always been ripe for treatment. From the 1970s through the 1990s, the U.S. saw a rise in crime, especially in cities, and the cinematic results have been diverse and long-lasting, from the seedy urban gangster movies inspired by Prohibition-era organized crime like The Untouchables to the urban cop dramas Serpico and Klute. And then there’s horror, a genre that at its heart exploits our anxiety about being helpless in the face of ruthless murderers — see The Silence of the Lambs and The Shining, a film famously snubbed at the Oscars.

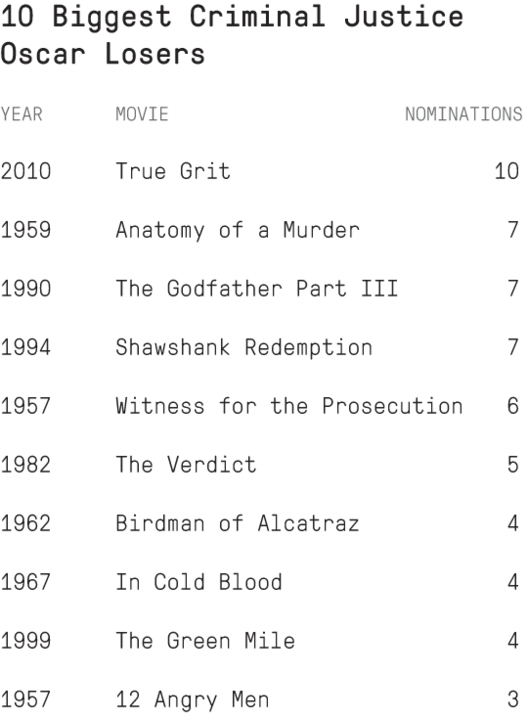

Though never dramatized directly, one result of the prison boom was a countercurrent of films depicting prisoners with very long stays behind bars, classics of the 1990s like The Shawshank Redemption and The Green Mile. Both of these films owe a debt to Birdman of Alcatraz, which in 1962 was way ahead of its time in depicting a man dealing with the psychological torment of solitary confinement. (It should be noted that all three movies were nominated, but didn’t win.)

Here are a selection of films worth calling out for what they tell us, and don’t tell us, about the real-life world of criminal justice.

12 Angry Men (1957)

Do you dread being called for jury duty? Is it because you’re worried about getting drawn into an endless, complicated debate? That’s arguably the result of this play-turned-film, which in 1957 was nominated for three awards and shows how one juror who believes in a young man’s innocence overcomes the intransigence of his fellow jurors. In reality, the scenario usually plays out the opposite way, with a majority of jurors overcoming the misgivings of the minority. Research from 2007 by Cornell Law professor Valerie P. Hans found that roughly 5 percent of jury deliberations involve the kind of come-from-behind situation depicted in the film. “Majorities usually rule,” Hans wrote, “but both jury research and the fictional jury depicted in 12 Angry Men confirm the possibility of a minority prevailing against an otherwise unanimous majority.”

My Cousin Vinny (1992)

Joe Pesci plays a lawyer with little experience tasked with defending his cousins in a murder case in Alabama and getting the charges dropped. Unsurprisingly, a lack of lawyerly experience has led to some horrific results that are now familiar to criminal justice-watchers, especially, as Yale law professor Stephen Bright has written, in the south, and especially in death penalty cases. Recently in Huntsville, Tex., a 25 year-old lawyer less than six months out of law school was allowed to represent a man facing the death penalty. The district attorney actually opposed the lawyer’s involvement, because he was worried about how a bad defense might lead to a reversal on appeal — a waste of prosecutors’ efforts and taxpayer dollars. Much as in My Cousin Vinny, had the accused taken a court-appointed attorney rather than hiring one of his own, he would have gotten a more experienced defender.

Serpico (1973)

“The police are still out of control” is the title of a recent essay in Politico by Frank Serpico, who was depicted by Al Pacino in the Oscar-nominated film. With that essay, the former cop has become a linchpin for debates about police conduct in the wake of the deaths of Eric Garner and Michael Brown in New York and Ferguson, but his message has not been quite as influential as his Hollywood name-recognition might imply: Recent polling has shown that a majority of Americans (56 percent) still trust the police. That percentage drops down to 37, though, for African Americans.

To Kill a Mockingbird (1962)

Still considered one of the greatest courtroom dramas of all time, this adaptation is the authoritative snapshot of how the criminal justice system — particularly in small, rural counties in the south — has railroaded blacks for crimes they have not committed. It’s usually treated as a historical artifact, though attorney Bryan Stevenson, in his recent memoir, Just Mercy, begs to differ. In the late 1980s, Stevenson, who is on the advisory board of The Marshall Project, represented Walter McMillian. McMillian was charged with killing a white woman in Monroeville, Ala., the hometown of the novel’s author Harper Lee. “Sentimentality about Lee’s story grew even as the harder truths of the book took no root,” Stevenson writes, arguing that McMillian, an innocent man, was denied due process when he was erroneously found guilty.

Capote (2006)

Though few films take on the justice system, even fewer look at reporting and writing about crime and punishment. Capote, which won its star Philip Seymour Hoffman an Academy Award for Best Actor, is a rare exception. In reality, the writer Truman Capote played fast and loose with journalistic ethics — and factual accuracy — when he wrote In Cold Blood, his seminal 1965 non-fiction book about a shocking murder of a rural Kansas family. Calling to mind the writer Janet Malcolm’s treatise on journalistic heartlessness, The Journalist and the Murderer, the film shows how Capote abused the vulnerability of a man in prison for murder to mine emotionally lurid details. Hoffman is able to make the great New York writer look somehow worse than the man whose crime he is writing about.