When people move away from a troubled neighborhood, do they become more likely to avoid crime and live a productive life?

For years, social scientists believed — often reluctantly — that the answer was no. Beginning in 1995, a large federal experiment called Moving to Opportunity provided housing vouchers to families living in extreme poverty in Baltimore, Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles, and New York City. Some of those families were required to use their vouchers to rent an apartment in a neighborhood where fewer than 10 percent of residents were poor. The hope was that children in those families would do better in school, obey the law, and eventually become middle-class adults. But that didn’t happen. Over the long term, the sons of Moving to Opportunity families were actually more likely to be arrested and to use drugs than boys in the control group who continued to live in poorer neighborhoods. Their incomes remained low.

But now a spate of high-profile new research seems to be overturning the Moving to Opportunity consensus. Moving from one neighborhood to another, it turns out, can have a big impact on crime and incarceration, as well as on individual earning potential. The key factor may be timing that move to the right moment in a person’s life.

The latest contribution to this research is from David Kirk, an American sociologist at Oxford University in England. His new study, which appears in the academic journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, took advantage of what social scientists call a “natural experiment” — a case when a real-world event creates random change. In this case, the event was Hurricane Katrina. Kirk first started thinking about its impact on the people who commit crimes in late 2005, when he visited storm-ravaged New Orleans to spend time with his in-laws, who live there.

“Driving around the city, it was hard not to contemplate the nature of the devastation and what it meant for individuals,” he said in an interview. “Certain neighborhoods didn’t really exist anymore. So where were folks coming out of prison going? They would normally go back to the Lower Ninth Ward or Mid-City, but they couldn’t. Where were these individuals?”

Kirk set up a study to find out, examining state data on where 5,400 parolees lived after leaving prison in 2005 and 2006. It turned out that after Hurricane Katrina, parolees dispersed throughout the state, often ending up in even poorer neighborhoods than the ones they had come from in New Orleans. They typically moved to smaller cities like Baton Rouge, Shreveport, and Lake Charles.

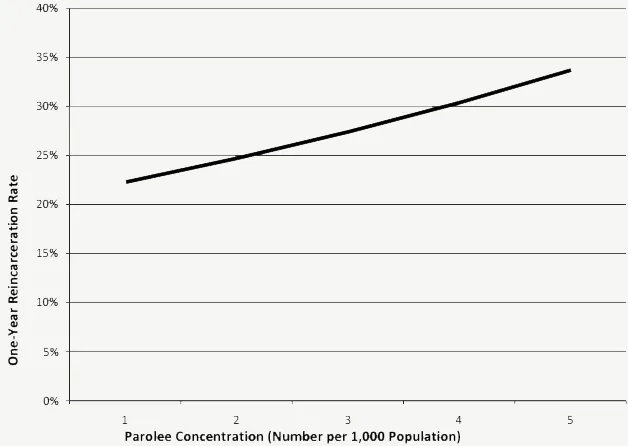

Previous research had found that former prisoners who return to poor neighborhoods are more likely than those who return to middle-class or affluent areas to end up back in prison, regardless of those former prisoners’ individual characteristics. But in a series of papers, Kirk revealed a surprising pattern in Louisiana after Katrina. Regardless of neighborhood poverty, the density of parolees living within a zip code had a powerful effect on whether recently released prisoners were able to turn their lives around.

In neighborhoods where five of every 1,000 residents had recently been released from prison, 34 percent of parolees returned to prison within one year, either for committing a new crime or for breaking the rules of parole. In similarly poor neighborhoods with just one recently released prisoner per 1,000 residents, 22 percent of parolees returned to prison. In a forthcoming paper, Kirk will look at Louisiana parolees eight years after their release from prison. The positive influence on these individuals of new neighborhoods with fewer parolees persists over time, he said.

Kirk speculates that moving helps former prisoners sever ties to people likely to become criminal associates. “Residential change is a turning point that may give people a fresh start,” he said. “It’s something that organizations like Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous talk about: Stay away from the people and places associated with prior behavior. In that sense, this is not entirely novel.”

Kirk’s findings join a widely heralded new series of draft papers from Harvard economists Raj Chetty, Nathaniel Hendren, and Lawrence Katz. They reassessed the decade-old Moving to Opportunity data in order to isolate only those children who were youngest — under the age of 13 — when their families moved. Staying in a high-crime neighborhood reduced reduced boys’ future incomes by 7 percent and girls’ future incomes by 4 percent, relative to kids who moved from high-crime to low-crime neighborhoods early in childhood and later earned more as adults.

That research is ongoing, and it is not yet clear if young children who left high-crime areas also experienced lower arrest rates. But the overall trend among sociologists, economists, and political scientists is to rethink the power of helping people change where they reside, especially during those periods of life, such as early childhood or the first year out of prison, when people are most vulnerable and also most heavily influenced by the social environment around them.

“The pendulum has swung back to thinking that neighborhoods are very important,” said Jonathan Rothwell, a fellow at the Brookings Institution who studies urban policy.

Housing vouchers that can be used only in neighborhoods far from the parolee’s original home could help former prisoners avoid ending up back behind bars, Kirk suggests. So could overturning state laws that currently require some parolees to return to their previous counties. Yet other scholars urge caution. A separate body of research on prisoners reentering society shows that family, friends, and former employers are the people most likely to help a recently released prisoner get a job, and that getting a job is a primary factor in avoiding re-incarceration.

“I have concerns about the policy implications” of Kirk’s Louisiana study, said Nancy La Vigne, director of the Justice Policy Center at the Urban Institute. “If the implications are that we should ensure that people, upon release from prison, are dispersed throughout a state, will it compromise social support networks in ways that make it more difficult to successfully reintegrate? What we know is that family members are there for returning prisons and provide emotional and tangible support.”

For Kirk, the key is recognizing that neighborhood-based social networks often exert a negative influence, in addition to a positive one. Previously, he studied the effects of “legal cynicism” in Chicago — perceptions of law enforcement as unresponsive and illegitimate — which appeared to contribute to high homicide rates in certain neighborhoods even as they gentrified. That type of cynicism, he posits, may blossom when many recently released prisoners gather in a small geographic area.

“Families aren’t always positive influences,” Kirk said. “Somebody has a brother or a cousin who is into drugs or worse, and that’s not good to be around. A next step on my agenda and in the field in general is to look at what residential change means for social networks. Can they help maintain positive relationships and end negative ones?”