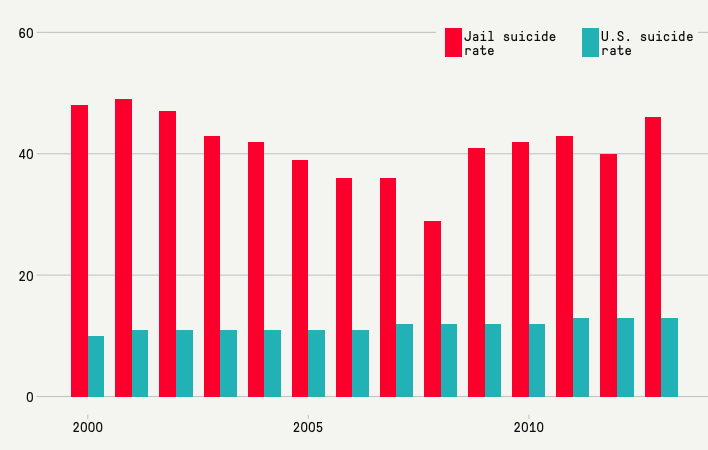

A report released today by the federal Bureau of Justice Statistics shows that among the causes of death behind bars, suicide in county jails — a leading cause of death in such facilities — is on the rise. These statistics, collected between 2000 and 2013, come in the wake of Sandra Bland’s death at the Waller County jail in east Texas, which received national attention and is currently being investigated by the FBI and a panel of lawyers for evidence of wrongdoing.

One reason why jails have a higher suicide rate (46 per 100,000 in 2013) than prisons (15 per 100,0001) is that people who enter a jail often face a first-time “shock of confinement”; they are stripped of their job, housing, and basic sense of normalcy. Many commit suicide before they have been convicted at all. According to the BJS report, those rates are seven times higher than for convicted inmates.

Jails also have less information to work with when they try to assess new inmates for suicide risks. “Prisons know who they’re getting,” said Michele Deitch, a professor at the University of Texas's LBJ School of Public Affairs who testified last week at a Texas Legislature hearing over the death of Sandra Bland. By the time someone arrives in prison, mental health issues — including suicidal tendencies — have had time to surface.

In addition to suicide, a primary cause of jail deaths, and one that can be linked to failures in the intake process, are deaths related to drugs and alcohol. BJS found that jails have had increased rates of “drug or alcohol intoxication deaths” in recent years2.

Although jails have improved their intake protocols over the past several decades, these protocols remain far less robust than in state prisons, which, Deitch said, “are shaped by years of litigation and the demands of the state legislature.” Prisons are more likely to have their policies scrutinized by an accreditor like the American Correctional Association. When a scandal — a suicide, or a wrongful death at the hands of guards — hits a state prison system, the entire state may change the way inmates are handled.

In 1980, Judge William Wayne Justice ruled in the massive prisoner rights lawsuit Ruiz v. Estelle and found that the Texas prison system, which now includes roughly 150,000 prisoners, had “no program whatever for the identification, treatment, or supervision of inmates with suicidal tendencies.” After that ruling, the agency was forced to screen incoming inmates for their risk of suicide.

Often small facilities never get sued at all, even in the wake of a suicide caused by negligence. “Cases tend to focus on big facilities because that’s where we can help the most people,” says Amy Fettig, an attorney with the American Civil Liberties Union’s National Prison Project. “But to do all these little jails, which would take the same amount of resources, it’s just impossible, and so nothing gets done.” According to several prior BJS studies, the nation’s smallest jails have a suicide rate more than six times as high as the nation’s largest jails.

Many advocates point to a lack of statewide organizations that could force jails to improve their procedures before they get sued. Texas has a Commission on Jail Standards, with four inspectors for the state’s roughly 250 jails. New York has a Commission of Corrections, with 15 inspectors for more than 500 jail and prison facilities, and California’s Division of Facilities Standards and Operations has nine inspectors for more than 600 facilities. The missions of these government bodies vary, but as Deitch wrote in a 50-state survey several years ago, “formal and comprehensive external oversight — in the form of inspections and routine monitoring of conditions that affect the rights of prisoners — is truly rare in this country.”