Watch our collaboration with NBC Nightly News, “Colorado's New Law to Hold Rogue Police Accountable.”

“This has to stop.” Mari Newman had been saying that for years as she fought in court against police brutality. The Denver civil rights lawyer had won verdicts and settlements for people abused by officers, and won awards for her work, too. But police departments and their officers’ behavior didn’t change.

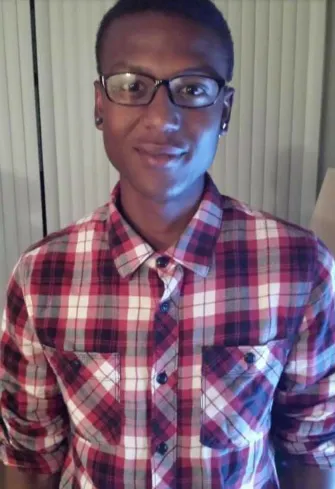

The final straw for her was her latest job, representing the family of Elijah McClain, a 23-year-old massage therapist who was stopped by police last year while walking home after buying iced tea in Aurora, Colorado. Officers responded to a 911 call from someone claiming a Black man “looked sketchy.” When McClain asked the officers to leave him in peace, they used chokeholds to pin him to the ground and had him injected with a powerful sedative. As the unarmed, handcuffed man vomited and begged for his life, police threatened to sic a dog on him. McClain was taken to a hospital and died there a few days later.

“I was pissed off and frustrated,” Newman said recently. So she called a longtime friend who had the power to do something: state Rep. Leslie Herod. The two women met for drinks, shot some pool—and hatched a plan for what real police reform would look like.

Colorado passed the final version of these sweeping changes in June, including one drawing national attention: Now police officers who violate people’s civil rights can be held personally responsible in state court.

And they can’t use the defense that experts say has stymied many efforts to hold police to account: “qualified immunity.” It’s a legal doctrine that says government workers can’t be held liable for what they do on the job, except in rare circumstances.

Some legal experts are praising the new law. “Colorado has passed what is, for the moment, the gold-standard reform,” said Robert McNamara, a senior attorney at the Institute for Justice, a libertarian non-profit. “These laws are changing the status quo as to when there are consequences for bad behavior.”

But the change is drawing fire from police unions, which say qualified immunity is essential to protect their members from being sued for doing their jobs, and from some local governments which fear it will hurt their abilities to recruit and retain officers. At least one insurance company is trying to come up with a plan that would protect cops from having to make personal payments if they lose in state court.

Since shortly after the Civil War, Americans have been allowed to sue law enforcement or other government officials they believe have violated their Constitutional rights by, for example, using excessive force. Most of these cases have been brought in federal court (state courts have traditionally had weaker civil rights protections).

In 1967, the Supreme Court carved out a “qualified immunity” exception that helps government officials: They couldn’t be sued if they were acting in good faith and didn’t know what they were doing was illegal. Over the years, the court expanded that doctrine so that now, even police officers who knowingly violate someone’s rights are protected—unless a court has ruled that their behavior was unconstitutional in a previous case involving nearly identical circumstances.

Last year, for example, a federal appeals court found that a police officer who shot a 10-year-old by mistake while aiming for the family’s dog was protected from liability under qualified immunity. The judges ruled that he couldn’t be held responsible because there wasn’t a previous case where an officer was found at fault in almost identical circumstances.

Qualified immunity has blocked lawsuits for people who were killed by police during arrests; a man who was shot and killed after a 911 dispatcher put him in harm’s way; and a man who gouged his own eyes out in jail after he was denied mental health care.

A political mix of civil rights advocates and civil libertarians has taken aim at qualified immunity, which Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor has criticized as an “absolute shield” for officers accused of brutality.

In Colorado, the American Civil Liberties Union backed legislation earlier this year that would have done away with the qualified immunity defense under state law, but the bill failed.

That effort, combined with Elijah McClain’s death, inspired Newman to try again. “Qualified immunity has been an obstacle to justice for many people for a very long time,” she said.

Newman and her longtime friend Herod, a Black woman who is vice chair of the House Judiciary Committee in Colorado, built a bill using some of the state’s most egregious examples of police brutality as a guide for what practices needed to change. Some of their police accountability work ended up getting support from a broad coalition ranging from the ACLU to Colorado’s Fraternal Order of Police. Chokeholds are now banned, and most cops must keep their body cameras on during encounters with the public. However, ultimately the Fraternal Order of Police did not support removing qualified immunity.

The new law also made it easier to sue at the state level and bar qualified immunity as a defense for cops. The hope is that it will be easier to hold officers and their employers accountable in state court. If other states follow suit, people will likely bypass federal civil rights lawsuits in those places altogether.

In addition to prohibiting the defense of qualified immunity, the law also says that if officers lose in state court, they may have to pay 5 percent of damages, up to $25,000, of their own money. The state can also revoke an officer's certifications, banishing them from any local policing job in the state, if a criminal or civil court finds them liable for using too much force. Cops who fail to intervene when colleagues use excessive force can also lose their badges.

The law was designed to make sure victims of police violence like McClain’s family have an easy path for payouts, Herod said, and make it easier to remove abusive cops from the profession by revoking their certification.

"We can’t bring a life back,” she said. “But if we’re going to do something in someone's name and someone’s legacy, it better be bold and make a real difference."

Despite the wording of the Colorado law, experts say it is unlikely that many police officers will have to empty their bank accounts to pay for bad behavior. Insurance companies and taxpayers are more likely to be on the hook.

Local leaders—not an independent oversight agency—will decide whether an officer acted in good faith and therefore doesn’t have to pay damages, said Chief Cory Christensen, who heads the Steamboat Springs Police Department and is also president of the state’s Association of Chiefs of Police.

So cities and counties will continue to pick up the costs for abusive police behavior unless local officials rule that an officer was not acting, as the legislation says, under “reasonable belief that the action was lawful.”

Christensen said Steamboat Springs, a ski resort town in the Rocky Mountains, plans to have the city manager and city attorney review his recommendation as to whether an officer acted in good faith. If they don’t agree, city officials can override his decision.

“Each community has to figure this out for themselves,” said Christensen who, along with police union leaders, negotiated the bill’s language with lawmakers. The officer payment is capped at $25,000 rather than the $100,000 lawmakers originally sought.

Christensen said he doesn’t think the new legislation will deter problematic officers from unnecessary violence. “Bad cops are bad cops,” he said. “They already have policies that they don’t follow, they already have training that they are not willing to follow. They don’t give a hoot, and they don’t care about the money.”

In Denver, the “good faith” question will go to the head of the city’s Department of Public Safety, which oversees the police. The decision will be “based on the facts and circumstances of each case,” said Kelli Christensen, the agency’s spokeswoman, who is not related to Chief Christensen.

In Greenwood Village, a wealthy suburb south of Denver, officials announced they would shield any of the city’s cops from personally paying a lawsuit tab; the new law leaves the decision on whether individual officers pay in local hands. A spokeswoman declined to comment, but referred to the city’s explanation on its website.

“Incurring a financial penalty decided by a City Council potentially influenced by media and passions of the day is a far greater risk than many of our police officers are willing to take,” the statement said. “The principle behind such penalties can destroy the will of our officers to serve the people that they have sworn to protect.”

The legislation took effect on Sept. 1. This month, lawyers expect to file the first lawsuit under the new law, alleging Aurora police used excessive force when ordering a mother and her four children on the ground at gunpoint earlier this year.

Colorado state and city government officials said it’s still too soon to tell how many cops could be forced to pay victims or leave the profession for bad behavior.

Denver’s Assistant City Attorney Wendy Shea told a policing think tank that the city may become more likely to settle abuse complaints against officers rather than risk taking these cases to court. “Essentially they lose their job if we take it to trial and lose,” Shea told The Police Executive Research Forum in Washington. Through a spokesman, Shea declined to comment.

The nation’s largest police union, the Fraternal Order of Police, said the organization supports the idea of decertifying bad cops if there’s evidence to back it up.

But Rob Pride, a Colorado police sergeant who is the highest ranking Black member within the national union, said he opposed stripping away qualified immunity as a defense for cops.

“People think that police officers have a free reign to do whatever they want and they are not held accountable; that’s not what it means,” he said. “It does not prevent police departments from firing officers.”

Police-union members in Colorado voted to raise dues to pay into a legal defense fund to help cover the costs of any upcoming payouts, Pride said.

Prymus Insurance in Texas asked Deborah Ramirez, a law professor and police-accountability expert at Northeastern University's law school in Massachusetts, to analyze how much personal liability insurance should cost for cops in Colorado. Her law students are building a database of payouts for police cases based on records from the state’s five biggest cities.

“We can’t price the risk if we don’t know what the risk is,” said Jeff Harrison, Prymus’s CEO.

The policies could flag problem officers, he added. “We will have the ability to raise rates and make someone uninsurable,” he said.

New York City spent more than $220 million on police liability claims in the 12 months that ended in July 2019, according to the city’s comptroller’s office. In Chicago, police misconduct cases cost the city more than $113 million dollars in 2018, based on an analysis by the Chicago Reporter.

Joanna C. Schwartz, a qualified immunity scholar and UCLA law professor, found that local governments paid 99.8 percent of payments in police civil rights cases. Schwartz examined a sample of about 9,200 cases across the country over a six-year period ending in 2011.

Inspired by Colorado, a dozen state legislatures have considered ways to make cops more accountable for bad behavior. Lawmakers in Massachusetts passed a slew of police reforms in early December, including a narrow change to qualified immunity. But the Republican governor rejected the bill after police unions took out ads in local papers saying the changes would harm policing.

If the governor signs the bill, cops can be held personally liable for abusive behavior only if the state revokes their police certification as well.

So far, only Connecticut has passed a new law. As of July 2021, police officers there will have to pay for their own lawsuits, and related damages, if a court decides that the officer engaged in a “malicious, wanton or wilful act.”

But right before signing the bill into law, Gov. Ned Lamont told reporters: “Qualified immunity is in place for the vast majority of anything a cop could be doing.” Lamont described the chance of an officer having to pay for a lawsuit as “incredibly rare.”

In New York, state Sen. Alessandra Biaggi introduced a bill this summer requiring that local cops carry personal liability insurance. If cash-strapped local governments “are still being forced to pay out police misconduct cases, we are going to bankrupt municipalities,” said Biaggi, a Democrat.

In response, the NYPD patrol officers union tweeted that Biaggi wants to “make policing such an unattractive profession that nobody will do it.” Her bill has stalled in New York’s legislature.

Colorado’s law won’t help Elijah McClain’s family. In August, Newman filed a lawsuit on their behalf in federal court, where qualified immunity remains a defense.

The lawsuit alleges that although McClain wasn’t suspected of any crime, he died after police used deadly force on him and paramedics injected him with a massive dose of the sedative ketamine. Some of the officers were fired after returning to the scene of McClain’s death and taking mocking selfies. Yet if the court doesn’t find there’s an established case where similar actions are deemed unconstitutional, the officers may not be held accountable in federal court.

The City of Aurora has announced plans for reforms after intense public criticism of its actions in McClain’s death. But in its legal filings, the city is arguing that its employees are protected by qualified immunity so the family’s lawsuit should be dismissed.